Maybe I was thinking that if I don’t know about it, it won’t happen to me. But it did.

1 Say anything

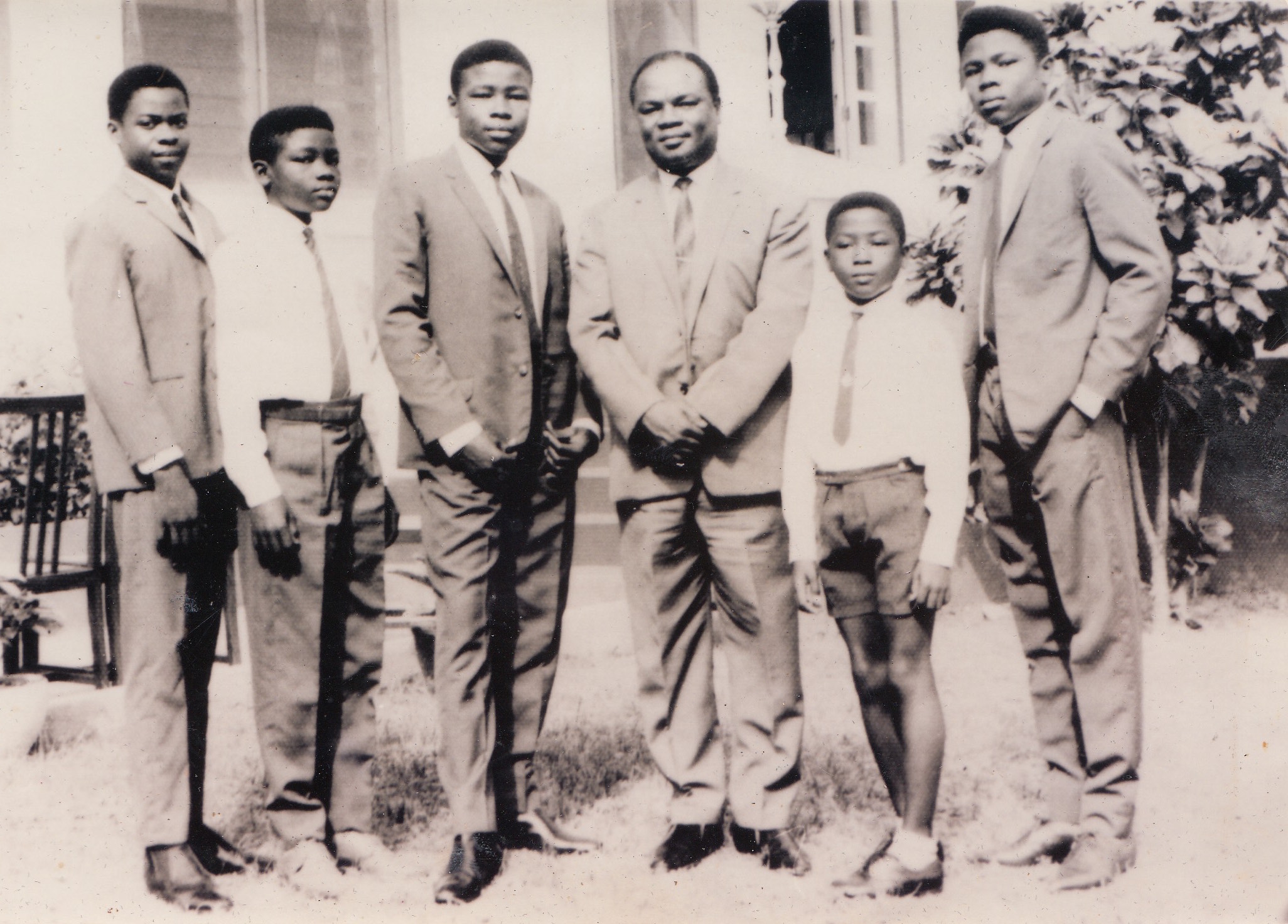

I met Adoley back home in Ghana. I was twenty-two. She was working a holiday job in my dad’s office. She lived across the road from us, and she came to my house one morning to get a lift to work with my dad. I came downstairs, just out of bed, and there she was.

How would you feel if you walked into your front room, first thing in the morning, in nothing but your pants, and you didn’t expect anyone there? I was thinking, ‘who is this?’ She sat there looking so pretty. I was looking sheepish. When you’re caught in a situation like that, you have to say something – you have to say anything. So I said something stupid like, "Do I know you?”, or “Do you know me?”

And she said, "I don't know".

My friend Theo was turning twenty-one that weekend, so I asked her if she was coming to his party. I knew she didn’t know Theo but I just had to ask, to get things going. When you’re in a hole, you stop digging, but I didn’t stop digging – I kept going on and on to make her talk. She wasn’t a talker. So I said, “If you want to come, I’ll knock for you.”

On Theo’s twenty-first, I knocked for her, and she was ready to go.

2 Pigs

We went out for ten years, and we got married in Aberdeen. She was doing her degree there while I was in Denmark on a university exchange programme. I was studying agriculture and working on a pig-farm. We’d raise the pigs for three months, and someone would come to buy them off us and raise them till they could go to market. The farmer’s son didn’t want to take on the farm – the farmer’s wife kept saying, “Magnus doesn’t want to be a farmer! Magnus doesn’t want to be a farmer!” I could have taken on the farm myself, and acres of land round it. But I thought, ‘No, I can’t work with pigs for the rest of my life.’ Pigs running through your legs, all that donkey-work. Maybe I could have done it. Nowadays my favourite thing to watch on telly is Escape to the Country.

When I moved to Aberdeen I was working as the night manager in a hotel. We had a contract with an oil company, so their workers would come and stay overnight before they went offshore. They made me so angry some times, pouring drinks for themselves behind the bar. I had to send them to bed. Working offshore is a dangerous job, so you have to think before you send off these young men with drink in them onto the rigs.

Eventually the hotel was sold, and all these women who had worked there twenty-odd years, they got a note telling them ‘the new owners will take you all back on’. But they were all laid off. The notes weren’t worth the paper they were written on. Old ladies, just laid off – and I’m thinking, what wickedness! This is their life. It’s a whole way of life for them, and you come and tell them they’ve lost it. We’d become like a family, we were so close. I wasn't having any of it. I was one of the few kept on, but when I saw my chance to leave I took it. Maybe that’s what made me interested in politics. I was thinking, 'there’s got to be a redress for these people.'

3 Good people

We moved to Hackney after we got married. I was involved with a lot of work in the community. My job was to help young people into work or training. I helped people who had just come to the country as well. You’d be surprised the number of people who are over-qualified for certain jobs but just wouldn’t have the confidence to go and do it. I had a girl from Lithuania come to me once, and the only work she wanted to do was to work in Harrods – I think it was the cosmetics counter – and she didn’t think she was good enough. “You’re more than qualified to do it,” I said. “You’ve got a second degree from Lithuania. What makes you think you can’t do the job? You’ve been here with me for two hours speaking in English. I understood you alright and you understood me. So what makes you feel you can’t sell lipsticks and nail varnish?”

I realised as I went along that a lot of these young unemployed people had problems with their housing as well – rent arrears, council tax arrears – and they were always being threatened with eviction. I had to stop that from happening. I actually represented some of them in court. I wasn’t a solicitor but I knew the law. I remember saying: “We’ve only just got a job for this young person and you’re going to throw them out and make them unemployed again – yet you’re funding this project which is supposed to help them find work?” I couldn’t just sit back and see these kids thrown out of their homes and end up in an even worse state than when they came to see me. Fortunately we won a lot of our cases. You can’t evict everybody.

I found my work stressful because it sometimes came with domestic violence. We realised women were coming in with black eyes – “What’s happened to you?” There were times when I realised my skills don’t go that far. You have to work with the people involved and you come face to face with them in the community. You’re actually telling someone to take up a case against their partner, and you bump into the couple shopping at the weekend. It happened once that one of the women’s partners threatened me. That wasn’t a nice part of the job. I could have easily moved away, but I love the area.

I don’t go out in the community as much as I used to. I don’t like people seeing me and feeling sorry for me. People stop you: “I feel sorry for you”, and “What’s happened to you?”, and “Why do things like that happen to good people?”

I used to run a youth club, summer schemes and things, and these kids are still asking me, “What are we doing this summer, what have you got for us to do?” But I can’t do that now.

They’ll see me, but it doesn’t register that I’m not the same person anymore.

4 Deadlines

The workload impacted on my family life. My wife had to give up a lot, and do a lot. I was doing something like twelve hours a day. We won £300 million from the government to regenerate five estates in Hackney [1], and I was a member of the committee overseeing the developments, especially on the Kingshold Estate [2].

I don't miss those long working hours, but if you've got work to do, you're going to have to do it. What's the use of sitting at home and thinking of the work you should have done the day before, the work that’s waiting for you?

Deadlines got the adrenaline going. Even though we were panicking – "Are we going to finish this thing, will the bid get to the government office before 5 o' clock?" – I loved all that. I miss the challenges and the camaraderie of work. Part of me really wants to go back to it, though another part tells me that will be too hard for me now. But at that time I thought, 'Nothing can touch me.'

People can turn against you when you take a job with the council. Working for the council is like working for the enemy. But the council have got all the cash: if you want something changed, you need to involve them. We were working with the police too, bringing them onto estates, into youth clubs, so these boys at our clubs would be on first name terms with the police, so they didn’t run from them anymore. You need that trust. There’s a lot of resistance – resistance to change. For some, this is their life, the life they’ve been living for a long time. Making money from drugs, this and that. The other day I saw some large foot-prints in one of our flowerbeds. This Bigfoot must have jumped over the fence and crashed onto our flowers. The next week I find a man stooping over my gas-meter box. “What are you doing?” He jumped up – “Oh, I was just passing by…” I know what he was doing – someone had planted drugs there, and he was collecting them. These kids, bored out of their heads, with nothing to do: you can see in their eyes that they’re up to no good, walking around with their eyes down, not making contact with anyone. Nobody’s getting up to give them something to do. I don’t have the energy for that any more. I leave them to their own devices.

Not very many people in the community know how to do things like ask for funding, and sometimes it frustrates me that people don’t want to do it. It’s only a matter of getting up and facing the people in authority who have the money.

I spread myself too thinly. There came a point when I realised that. I couldn't be everywhere at the same time.

I was having a lot of sleepless nights, because I could not switch off. Sometimes lying in bed, I would wake up, worried about running out of money for certain projects. I'd lie there thinking, “God, when is this money coming in?”

My wife said, “Slow down.” But I couldn’t slow down. The things I was doing needed to be done. She said, “I had a dream about you. I was standing at your bedside. You’d suffered a massive heart-attack or a stroke.” What she dreams, it comes true, so I was thinking – ‘Stroke or heart-attack? I’d rather have a heart-attack.’ That shows you how ignorant I was, not taking it seriously. There were things I should have known, doing the work I was doing. I must have met stroke-survivors, that kind of thing. Maybe I didn’t want to know, because I was scared that it could happen to me. Maybe I was thinking that if I don’t know about it, if I don’t get involved with all this, it won’t happen to me. But it did.

5 Human beings (Adoley)

You wake up early in the morning, and by the end of the day your life changes.

I was on a nightshift when the call came. It was summer and the kids were out at a barbecue. Witman was driving back from a meeting with a few others in the car and he complained of a severe headache. One of the passengers was a nurse and she recognised what was happening.

“Witman, I think you’re having a stroke.”

An ambulance came. At that point he was still talking.

Me, my two older daughters and some friends got a taxi to the hospital. We sat there for an hour waiting to see him. A Ghanaian nurse spotted us. “I think he's behind the screen here.”

They’d torn his shirt, and phlegm and blood were coming out of his mouth.

A nurse came to me. She said his blood pressure had gone too high – that’s the cause of the stroke. I asked the doctors what they were going to do for him. They said they didn't think he would survive until the morning.

My second girl was on the floor crying. She tore off her acrylic nails with her teeth. We started praying, praying, praying.

Later that night a team from the Royal Free Hospital came to transfer him there. We followed in a car. I think we got there at 6am. Witman was in intensive care. They gave him three days. If he doesn’t come out of the coma in three days, that will be the end.

Everybody was praying – praying aloud, standing next to him, talking to him. They said if you don’t talk, he will just slip away. So we were telling him how people are feeling, what’s going on around him. Telling him to hurry up and come back.

On the third day, they took him from intensive care to the step-down unit.

On the fourth or fifth day he had a fit. His tongue was black. He was stiff. He’d had convulsions. I called the nurse and said, "Something has happened. I think he’s dead." She ran over and cleared his airway. He took a quick breath and came round.

He'd had a tracheostomy so he couldn’t talk. He was pulling at his tubes when he came round, so they put gloves, like a boxer’s gloves, on his hands. When he wanted to talk, we’d give him a pen and paper to express himself. We were communicating with a notebook. He could hear, he was alert, but he couldn’t speak. We’d talk about everyday things: what’s happened to a friend, how things are going at school.

Before we left we’d all gather together and pray.

Pray for the doctor, pray for the nurse, pray for the cleaner. Pray that everything should go well. Pray that the doctor has the wisdom and understanding to heal the disease.

We are all human beings, and we see everyone as human beings, but we don’t always know how people are spiritually. Maybe the nurse has his own problems back at home. So pray that the nurse will see things differently. And pray for God to speed up the healing.

6 Who am I talking to?

I think I had memory loss. There were sometimes people I knew who’d come and stand in front of me in hospital, talking to me, and I’d be thinking: ‘who am I talking to?’ Then my wife would whisper to me: “This is such and such from work, do you recognise her?” I know I knew them, because they’d tell me their names, and I’d know their names. But I couldn’t recognise them. Terrible thing.

“Do you know who’s talking to you?”

“No, can you please help me – who are you again?”

“This is such-and-such.”

And I’m thinking “Oh – you’ve changed!"

I was in my hospital bed and there was a nurse who recognised me: “I remember you taking your two girls to school every morning." I told her that those two girls are both at university now, so it must have been more than ten years ago. I didn’t recognise her at all, but from what she said, I was always with my two girls. I was thinking, ‘I have never seen you before' – but it must be right because of what she was describing. How do you recognise me from my sick bed?

I’ve got to be honest, it makes you proud sometimes, when people come from all over the place telling you, “I know you from here.” The last thing I expected was for somebody to come up and say, “I know you.”

That’s why you must always be on your best behaviour wherever you go.

Roles have changed at home now. My wife has to do everything, all the paperwork and things like that. There are things I want to do for myself but I can’t – simple things like getting up and going to the bank. You’ve got to get somebody to do it for you, or someone to come with you, and I don’t want people interfering with my affairs. There was a time I used to do all this by myself.

Even basic things like getting out of bed are big challenges for me now. For a while I was flip-flopping out of bed, and my wife was like, "Will you stop doing that, you’re scaring me!” I’d be lying there and go flip, flip, flip and flip myself up. There are times I don't want to get out of bed. I'm just lying there.

7 If God wants to take you away (Adoley)

When we were praying, Witman said every prayer would prick him like a needle.

Prayer is a conversation. You wake up in the morning and say, "Thank you God, I am alive." Witman woke up in the morning, and at 11 o’ clock he had a stroke.

Some people went to bed, and then to the mortuary. If God wants to take you away, he has the power to take your breath just like that. But sometimes he wants to use you to touch others, and change others.

Before, most of Witman's friends would meet at the pub and make merry. But when Witman had his stroke, they all woke up and thought ‘maybe it’s getting too much’. It’s changed everybody. Everybody had to go and check their blood pressure. Everybody knew they had to eat well. They knew 'I don’t have to overwork myself, I don’t have to drink.' It woke everybody up. Witman was a strong, active person. You saw him on Friday night and on Saturday, he is like this.

So it touches others, and it changes others.

Our life has changed. I gave up my work to care for him. Benefits, social care, bring this, bring that, let us come in, here and there. You see a brown envelope and you panic. When the new financial year is coming, you panic. But the people at the carers' centre ease your pain. You know they are there to help. They make things comfortable [3].

The stroke has limited us in so many different ways. Have you seen that programme, 'What Life Took From Me'? It's a Mexican show, but we watch it on the African Broadcast Network. Well, this is what life has taken from us. It took away our freedom.

8 Talk from the heart

I’m not involved in politics anymore. I’m not a paid-up member of any party. Politics is dead. Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair killed politics in this country. In days gone by, Labour was Labour, SDP was SDP: now they all believe in the same things. It’s not interesting any more - it’s too uniform. Where are they now, the people who will argue, verbalise how they feel, speak their conscience, talk from the heart? Where are they now? Just gone. These days politicians are in it for their salaries. Now David Cameron says he’s going to give some money to help the worst estates. But the amount he's talking about is peanuts in the scheme of things. Maybe that’s enough for some cosmetic works: change a window here, a door there. Politicians talk so much rubbish.

If I was them, I’d focus on workers’ rights. Focus on a fair wage – what do they call it now? – a living wage, for workers. And on making sure disabled people are taken care of. I’ve been disabled eleven years now. Disabled people are treated very poorly. The government are always having a go at us, always attacking disabled people. They don’t know how hard it is. I don’t need encouragement to work – if I could, I’d make work for myself.

As a disabled person, you’re always under suspicion, from the government and from the Sun newspaper. This government is a government for readers of the Sun. These stories you hear – someone’s claiming disability benefits and refereeing at football matches on Sundays, running up and down, whatever it is. There will always be one who plays the system, but that doesn’t mean everybody’s doing it. Don’t smear every disabled person.

9 Is it Lazarus? (Adoley)

In the bible, when Lazarus wasn't well – is it Lazarus? – his friends heard that Jesus was in the town healing people, but they didn’t know how to get him through the crowd. So they took off the roof, and they lowered him down. It was the faith of his friends that helped him to get well.[4]

Some people don’t recover. They drop, and that’s the end of it. It was our faith that pulled Witman through. It’s the people around you who will help you.

Mark 2

1 And again Jesus entered into Capernaum some days later, and it was reported that he was in the house.

2 And straightway many were gathered together, insomuch that there was no room to receive them, no, not even about the door; and he preached the Word unto them.

3 And they came unto him, bringing one sick with the palsy, who was borne by four.

4 And when they could not come nigh unto him because of the crowd, they uncovered the roof where he was. And when they had broken through, they let down the bed on which the one sick with the palsy lay.

5 And when Jesus saw their faith, he said unto the one sick with the palsy, “Son, thy sins are forgiven thee.”

10 Gifts

Our daughter got married on Saturday. It was beautiful. People have been phoning up to thank us. I should be thanking them for coming and making it a beautiful day. We had African drummers and jugglers and dancers. I can’t move as well as I used to, but I danced a bit. I was a good dancer in my time. My brother came over from France and he kept getting the dance steps confused – they’d call out "Put your right leg up!" and he'd put up his left leg every time. We were all laughing.

Part of the traditional Ghanaian ceremony is the receiving of gifts. I ask my daughter, "Do you want me to accept these on your behalf? Do you want to go with this man?" She says yes. And I say, "Come on then – more gifts!"

© 'Witman and Adoley' / Headway East London (2016). All rights reserved

Photo portraits by Andy Sewell

Additional photos by Conor Cotter and Chris Dorley-Brown

To support Who Are You Now? and the work of Headway East London, please text WAYN61 followed by an amount to 70070 or donate online.