He used to ask me to lift a bottle in my hand. I’d say, “You must be joking!” I couldn't even extend my hand. He’d say to me, “come on Trudy, lift it, lift it!"

1 A lottery

It was Christmas Eve 2010. We went to do some shopping at the supermarket and I remember it was full of people and boxes. I tripped over a box and I was really annoyed; whether I tripped because of pre-stroke symptoms, I don’t know.

We came back home and had a cup of tea, and Steve, my partner, said he was going down for the Lottery ticket. We were laughing because an Irish girl had won £20m on the EuroMillions lottery. I remember I called him back – I don’t know what I was going to say to him. He came back and we were laughing again. And then I called him back a second time, and that’s when I had the stroke.

Steve knew immediately. I was in the downstairs loo and I’d smashed the ceramic toilet roll holder. He could see my face was down and my hand was down on one side. I felt exhausted. He says I was slipping from consciousness. I remember I wasn’t; we still have that argument. He rang the ambulance straight away and he rang my daughter – she was at her boyfriend’s at the time and she came running over.

They stabilised me in the ambulance. My nearest hospital was full, and the Royal London was full. It seemed to be like the Nativity: no room at the inn. And the paramedic said “what will I do now?” They decided to take me to University College Hospital in Euston. I remember all this going on around me, as well as anything.

There isn’t a good time to have a stroke but it was particularly busy. It’s very easy to knock the NHS but you can’t legislate for how busy it’s going to be – it’s a lottery. We even had an accident; the ambulance crashed on the way up to UCH!

The stroke nurses and the consultant were ready for me and they were very good. Whether or not it would have been better to go to the local A&E, which is about five minutes away from me, whereas UCH is twenty-five minutes away, I don’t know, but what can you do? There’s no point in looking back.

These days I can’t wait until Christmas Eve is over; it’s not logical, but I’m watching the clock.

2 The dog

Steve thought I would die that night. But I remember, God love him, he stayed there all night. And then he went home and I slept. I remember sleeping a long time. And he and my daughter were there again the next day, all day.

I was very paralysed. I was on an IV drip and I had a nasogastric tube. I didn’t have a swallowing reflex for a week. Every day the nurse tried and it wouldn’t come back. I couldn’t swallow. One day she tried me one more time, and I was able to swallow fluid, but the muscles were very weak.

They transferred me to my local hospital in a wheelchair. It was very uncomfortable, the journey there, in a big old ambulance with all the seats. They put me into a male ward, and I sat in there for the whole day. And then they put me into a female ward and they were all elderly, some with senile dementia. I couldn’t get out of the bed, and I couldn’t do anything, and I couldn’t sleep because they had to turn the older people every two hours to prevent pressure sores, and every few hours they’d change them. They used to tell me, “don’t get off the bed on your own!” It wasn’t that they ignored me but they were very busy.

I remember Steve came in one evening and I was really fed up. Steve went up to the charge nurse – he was a male charge nurse from Northern Ireland – and said, “if you don’t do something, she’s going to discharge herself” (although where I was going, I’m not sure about!) The nurse thought about it and came back with a wheelchair. He said, “sit her into that and take her all over the hospital.”

He saved my life, that fellow did. Every evening Steve took me all around the hospital and we would look at the pictures on the wall or we would go to the canteen. My sense of humour came back to me. It was freezing cold, but Steve used to wrap me up in loads of clothes and take me out to the car to see the dog. He didn’t know where I’d gone, the dog, you see. He was pining for me.

After that, I went along slowly but surely. I used to hold on to the side of the bed and drag myself along, and slowly but surely I got back the use of my leg. But I couldn’t move my hand. I never knew I’d be able to move it like this.

One of the doctors told me that if you don’t make progress after three months, you won’t make progress at all, which is ridiculous. I don’t know why I got this notion, but I did: I thought that after three months I would suddenly wake up and be perfect. Now why my logic told me that, I don’t know. I was an experienced nurse but I was blindsided. The doctors were in the position of authority, and I lost a lot of my ability, I think, to – not remain neutral, but – to intellectualise it, really. And then when my emotions came back to me I thought, ‘they were rubbish, these professionals.’

3 An archaeologist of the mind

I told my mother I wanted to be a nurse when I was a child and she held me to it, I think. I would never go into that now. I wanted to study archaeology, but even though I did lots of archaeological digs when I was a child, they were all amateur. The Viking settlement at Wood Quay in Dublin was being excavated, and the digs were done near the convent school I went to. I went up to them and said “could I get involved? The summer’s coming up and I want to do it.” I always thought it was something I would do as a hobby, you know. It never crossed my mind it was a profession. And that was a mistake I made, really. But ah, well. Eventually I ended up training as a psychotherapist – an archaeologist of the mind.

My father didn’t want me to be a nurse. He’d say, “I don’t think much of that. Too many women in that profession for you.” My father knew I was someone who says it straight, and he thought I wouldn’t have a chance in that situation. Maybe he was right.

He said I should join the convent, get them to train me as a doctor, and then leave. My mother used to go mad! “You’re filling her head with nonsense!”

My father was a remarkable man; well, I think he was remarkable. He had a knack of making every one of us feel special. Each of his children spent time with him in a different way. He used to build wheels for scrambling bikes, and he’d go out on his motorbike every weekend – I used to go with him then.

He was a chemist and an engineer, and a gunsmith as well; he had a big huge shed in the garden with all of his tools and chemistry equipment. He made beer and fermented it in the airing cupboard. And it would stink; oh, jeez, it stank! He would supply half the county with cough syrup. It was only what he’d make himself, to ease the throat or ease the chest. We would have a knock on our door, eleven o’clock at night. “Is your father there? Could I have a word with him?” A lot of people wouldn’t have the money to go to the doctor.

4 The right thing at the right time

After my training, I went to Madrid and worked in neurology research. I’d never seen anything like Madrid. It was mindblowing because Ireland was very homogenised back then, very different from what it is now.

That changed my life completely, I think. I was never contented with Dublin any more after that. I wanted to travel and explore.

Really, I packed a lot in very quickly in my life. I lived in Holland and in America. I started working in London and I was very quick at picking things up so I was only a staff nurse for nine months and then I went to ward manager. And I went up and up until I was nursing director when I was about twenty-seven. Then I got disillusioned, I think. I realised you had to watch your back when it came to funding and money. Margaret Thatcher was in power, and it was awful. I was constantly aware of the need to say the right thing at the right time, and I couldn’t be honest. I realised it was a game, rather than a system that encouraged you to think about patient care.

Then I trained as a community psychiatric nurse. It was around the time of Care in the Community and it was a big thing for me at that time. I ended up managing the community social workers and community nurses. There’s a big need and there’s very little you can respond with; you have to manage the funding. I did enjoy my career, but I didn’t, if you know what I mean.

I was always studying something, and working at the same time. I got a place at Cambridge to study law, but I didn’t take it up. I couldn’t make up my mind what I wanted to do, you see. That’s when I started getting interested in psychotherapy and around the same time I had my daughter.

I left nursing and I spent three years in training as a counsellor and looking after my daughter. Looking after her was fantastic, but I had to do something besides.

I was always very busy. All of my life was busy; that’s my nature, I suppose.

After I trained as a counsellor, I worked in addictions and I ended up as a director in an organisation that did community detoxes, where people came every day, and they had groups and supervisions. On one level, I thought that I was really trendy to work in addictions – I was being a trendy left-wing nurse! I thought it was a departure for me but it wasn’t at all. I was interested in the therapy end of it but the counselling took a back seat because they needed a nurse. Once you’re a nurse, you’re a nurse.

I was very good at it. I was magic! They’d come to us and they’d be shaking and hallucinating, and oh, crikey, it was terrible. Their doctors often didn’t know what to prescribe for them. I remember one man, not long before I had the stroke, he was in bed and he was withdrawing from alcohol and he’d a coat stand in his room and he thought it was a woman. He used to get up out of the bed and go and look at it; he was shaking and delusional. I said, “what did the doctor give you?” and he’d say “he prescribed me this, this and this”, – and the doctor had it wrong. And once the prescription was sorted out he was grand. The medication, you see – I was so used to it at that stage – the medication had to be solved. And that’s when the addiction really took hold. They had to be face to face with themselves, I suppose.

I was very hands-on and very involved. That’s the type of person I am, I’d say. I have to understand every job in the organisation. If you don’t know how to wash the floor, I’ll show you, because I can do it as good as anybody, you know what I mean? By the time the end of the day came, it was then I caught up with all my emails. I always worked two hours after everyone else was gone.

5 Forthright

I went home for a day and I didn’t want to go back to the hospital at all. And then the following weekend I went home for two days. And Steve was supposed to take me back by about eight o’clock that night and I didn’t go back until well after nine. I didn’t want to.

But then they talked to me about discharge. I thought about it for a while and I said, “no way do I want you to discharge me to nothing. No way!” I said “I know what community teams are like. I know, because I managed them”. I knew that community teams were under-resourced. I think they were frightened of me by then, the physiotherapists and the occupational therapists [1]. I must have been a devil! I’d got the strength by then.

In the beginning they didn’t know I was a nurse, and I didn’t tell them, and I found that the minute I started saying it they pricked up their ears and listened.

The American occupational therapist, Nancy, said “we can guarantee we won’t discharge you to nothing.” She was very forthright – she was like me. It was for the fact that she was forthright that I got on with her. She was the best occupational therapist I ever had.

English people are quite polite, and they won’t push you too much. If I said I wasn’t in the mood that day or I was tired, the English physios would accept it. But then I got this Polish physio, Mateusz. He was different. He’d say, “come on, just try one little bit”. He used to ask me to lift a bottle in my hand. I’d say, “You must be joking!” I couldn't even extend my hand. He’d say to me “come on Trudy, lift it, lift it!” And that’s what I needed. That’s my personality, you see. I have to feel stimulated to do something. I did – I lifted the bottle and raised it to my lips.

Every time I meet him now we have a big cuddle. He was really something – he forced me and pushed me into getting back the use of my hand. He was powerful.

Community Stroke Rehabilitation Services

24th April 2011

Trudy was admitted to University College Hospital on 24/12/2010 with right-sided weakness and language difficulties. Investigations revealed a left-sided Middle Cerebral Artery infarct [2]. Once stable, Trudy was transferred for rehabilitation on 31/12/2010 and had approximately one month of rehab before being discharged home.

Trudy had significant weakness to the right arm, such that she had no voluntary movement. She also had subluxation [3] at the right shoulder, leading to marked pain in that arm. She was able to walk indoors independently but right leg weakness reduced her balance and confidence.

The outreach team was only supposed to see me about six months, but they came to see me longer than that. After I was discharged from the team they referred me to hydrotherapy and then the neurophysiotherapist at my local hospital. And then I was there one day and the physio asked me, ‘how would you fancy going for intensive physiotherapy? She needs the names today.’ It was a research programme with a neuroscientist. I was ecstatic. I couldn’t believe it.

I never realised the significance of the brain injury, but the neuroscientist showed me what a crucial part of my brain had been affected. She said, “looking at that now, I can’t believe that you’re the same person”. That says an awful lot to me, really.

It was like going to work every day. I did three days a week for six or eight weeks with the physiotherapist. It helped me an awful lot. I measurably improved. It was a coincidence that I was in that day, so that was another thing that I was very lucky to get.

I do think it has helped a great deal that I’ve been able to advocate for myself, because it’s led to these opportunities. I wouldn’t have improved as much as I have done otherwise.

6 Back to work

I believed that I could go back to work and everything would be fine. But when I came back on a trial basis, I was no good. Well, I was good but I wasn’t up to the level I was before. The stroke was a left hemisphere infarct, and it affected my communication, to an extent. My speech wasn’t as good as it is now, and I think I lost confidence in my ability to supervise staff and run groups. I think I was nervous and embarrassed, really. I was supervising counsellors and it was very difficult for me to get my point across. Writing was difficult because of my right hand – I still need to practise. And I think I suffered from fatigue as well, you know.

I think a lot of people didn’t know how to deal with me. I’m sure I was a force to be reckoned with before I had the stroke! Well, a lot of people think, if you don’t come across with all your faculties right, there’s something wrong with your ability to think. And that wasn’t the case at all.

I was only back a couple of days. It was around the economic depression, and there were a lot of changes around the company; I didn’t feel comfortable. I don’t know; it wasn’t the right time, anyway.

I always thought that eventually I’d retire, and I’d have a practice for myself, with time to pursue other interests. And that never came to fruition. That was the biggest disappointment; but there’s no point in looking back.

7 My companions

I get up very early because of the dog. He’s loopy, Spot. He’s my daughter’s dog really but he’s chosen to be with me. The cats are the same – sometimes when I’m watching television the three of them are on the bed with me. I’m a contradiction in terms. I say “no no, they shouldn’t be in the bedroom” – but they come in. They follow me all over the house and I love them – they’re my companions during the day.

Spot is very friendly with one of the cats. You should see them; they groom each other and everything. The cat and the dog, all day long!

8 A brilliant mind

I watched a documentary about a guy called Aaron Swartz. He was a brilliant little boy and he grew up and he went to university and everything got too basic for him. He was a genius. His concept was if there’s free internet for everybody then there’s freedom of choice and there’s freedom of everything. He killed himself because the government in America came after him in such a way… they made an example of him. He was facing nine years’ imprisonment for nothing at all. He was fragile – no-one picked up he was fragile – and he killed himself in the end. 26 is all he was. And all he wanted was for the world to be a better place and to have freedom of expression.

Really and truly, it blew my mind. Such a young life. Such a brilliant mind. He has a great following now but still his life has gone.

We never heard of him in this country. I couldn’t believe it. How did I miss him? We know everything about Atlantic Housewives and all these people that mean nothing to us. They’re pointless celebrities. It’s crazy.

9 A care receiver

I found it very hard to go from being a care provider to being a care receiver. Really, really difficult. I think there must be a lot of people who have worked in health and social care that refuse services after they have a stroke. I had to wait for a year to get funding to come to Headway. I didn’t want to come without the funding [4].

I was going to give up after about three weeks. I didn’t know what I was doing here. I suppose within the hospital we worked very strictly to timetables and I expected it to be the same here. I never stopped thinking like that. I worked a lot in rehabs and detox centres, and they’re very like here. You have the main space, there’s groups here, there are one-to-ones, and it’s all going on at the same time every day. Structure is very important to me. But I seemed to be left to my own devices and I was really annoyed.

I think it was the very first day; I was sitting at the table and I must have looked very downhearted. I was bored. Michelle said, “come over to the Art Studio” she said, “I’ll give you a canvas”. And she said, “try and paint something with your hands.” I painted an autumnal scene with trees and I was quite surprised. I’d done art for my leaving certificate and I only did it as an extra subject. So I’ve found my niche in the Art Studio. I’ve any number of paintings over there and I do a lot of art at home now as well.

I don’t make it obvious, but I help people. If Iris wants to go to the studio – I don’t make a fuss about it, but I’ll stroll over with her. I don’t know an awful lot about her condition, but she gets memory loss a lot, whereas my memory isn’t affected, really – very little of it is. I’ll somehow come across her sitting outside looking around, and I’ll say, “are you going back to the studio?” and she’ll say “yeah” and I’ll stroll back with her. I thought about this recently. I often say “I’ll take that to work with me.” I often call it work because I look at it that way.

I’ve resolved all my issues that I had when I came here first. I began occupational therapy here, and we had a psychotherapy group on a Wednesday, so I have got a lot out of it. It is a very unique place and it gives different people different things. But this is the conclusion I’ve come to now: I need something more at this point. I’m ready to move on forwards again.

Before the stroke, I was always doing something. Always and forever doing something. Steve is the same. Even if he’s busy at work, he’s always doing something besides. Working out a plan for this, or a plan for that. This is the only time in my life that I’ve not done anything, really, with my life, you know?

I want to fill my life with meaningful tasks. I think it would be a shame not to work with people because I have those skills – those skills are endemic in me! They’re not to be forgotten.

10 The Big Bang Theory

In the summertime Steve and I walk in the woods on Saturdays and go here, there and everywhere. But in winter I don’t bother. Too cold! I find this has always been my pattern: the winter takes an awful lot out of me. I lost five stone when I had the stroke and I find I get cold very quickly, and I don’t move around as much. We all have a duvet day but I have trouble to get out of the house. If I’m honest, if it’s raining outside, it’s harder to motivate myself and I come to Headway less.

I kept saying this winter wasn’t going to keep me in, but if the weather’s like yesterday I know I have the potential to get isolated. I’ll spend my time at home watching the goggle box and I don’t want to. I’m going to have to make myself go out. I want to prevent me from sitting at home watching true crime!

I wake up about half seven, watch the Big Bang Theory – I love that. It’s very good. And I love Frasier. I watched every episode twice, three times. He’s neurotic, Frasier. And the idiosyncratic behaviour of the two brothers mesmerises me. But anyway. The Big Bang Theory is about four nerds. Two of them are physicists and the competition between them is unbelievable. It’s hilarious. The situations they get into and the antics they get up to around women.

I find just as I finish watching those I drop off to sleep again. Then I try to make myself get up because I find that if I don’t get up early I don’t fall asleep when I go to bed.

Outreach Team Discharge Report

13th January 2014

Trudy was referred to the Outreach Team on 08/06/2011. Problems identified by her initial assessment were:

- -Regular falls

- -Fatigue [5]

- -Difficulty using home computer

- -Currently not involved in volunteering

- -Communication disability

- -Slowed processing of verbal and written information

- -Reduced recall of complex/lengthy information

- -Reduced stamina in reading

- -Word-finding difficulties

- -Some slurred speech (dysarthria)

- -Difficulty with handwriting

- -Exacerbation of communication problems by fatigue

Physical function/mobility

On assessment, Trudy presented with right-sided hemiplegia [6] and reduced right side flexion of the head and neck. Her right wrist is generally held in supination [7]. She has difficulty with multi-joint movements and fine motor tasks with the right arm such as writing. She has balance problems and significant weakness in her right ankle. When fatigued she tends to over-flex her right foot while walking, occasionally catching the foot on the ground. She has had a few falls indoors.

Cognition

Trudy has made a very good recovery in this area with the exception of her speed of information processing and verbal fluency, which are moderately impaired. Informal assessment suggests that her insight into current abilities and difficulties is improving, although she continues to underestimate the effects of fatigue on occasion.

Communication

Trudy presents with mild-to-moderate communication disability characterised by:

- -Slowed processing of verbal and written information

- -Reduced recall of complex/lengthy information

- -Reduced stamina in reading

- -Word-finding difficulties

- -Some slurred speech (dysarthria)

- -Difficulty with handwriting

- -Exacerbation of communication problems by fatigue

Her communication disability has significantly affected her confidence. She reported that she tends to allow her partner to speak for her in formal situations, including appointments and in the supermarket, but that she has begun to speak up more for herself.

I say I don’t suffer from fatigue, but I think there’s a bit of denial in that. I am exhausted when I come home from Headway on Tuesday and Thursday. But the other day I walked all over Paris with Steve and I couldn't have done that if I suffered from fatigue. Fatigue to me conjures up an awful lot more than how I present. After I saw the hospital outreach team recently, they mentioned fatigue throughout the whole report; they’d really made a big deal out of it. And Steve said, “you do suffer from fatigue, you know”. And I was disgusted! I suppose, really, it paints me in a bad light. I think it makes me look lazy, suffering from fatigue. I’ve never been a lazy person.

11 It wasn't for me

When you have a stroke, you don’t lose your ability to have a view. I want people to know that they can make decisions about their treatment themselves.

Until recently, I had Botox injections in my leg twice a year, but I found my balance got worse as the Botox wore off [8]. I was getting used to the Botox and then having to learn to use my leg again every time. In the long run, I decided it wasn’t for me. I felt it was better to do exercises to strengthen the muscles, rather than relying on the Botox, so I discharged myself from the clinic.

With Headway, I’ve given talks to healthcare professionals and students about my experience. I think it’s important that they see first hand that people can continue to improve over a long period of time. In telling my story, the one thing I want to get across is that there is no time limitation. You make your own chances. It’s important that medical professionals don’t have opinions that are too fixed, because it can affect your confidence. They say the more confident you are, the more chances you take.

12 The next situation

I just came back from holiday in Spain with my daughter, and that’s the first time I was without Steve since I had the stroke. And he’s going on holidays as well this year. There’s thirty-two of them from the company going out on a kind of jolly for a week to Benidorm; I pushed him to do it.

When I was in Spain I was walking round all the places on my own. It was really, really good. You know, I’m reliant on Steve when I’m at home; we link hands when we walk along the road.

In Spain, my daughter was there in case anything would happen but I had more opportunities to be independent. I decided I’d go off to the chemist and she let me go on my own. I took my time, and I crossed the roads at the crossing.

I went into the sea but I could only be buoyant for a little while. I’m sure I could keep myself up further, with practice. There’s something that attracts me about the water. I love it.

Funny; on the plane to Malaga there was a little girl sitting opposite me and she was playing a game called Milk Panic on the iPad. You have to milk the cows in this game. I was encouraging her, I was really getting her scores up, you know. And my daughter said to me, “I told you – you’ve no problem.”

Steve’s got me an iPad and he’s set up the iPhone for me. I’m playing with the iPhone at the moment until I’m confident – and this is my last week with the old Nokia phone. I suppose that the fact that I’m willing to give that up says a lot to me. I’m in the next situation now.

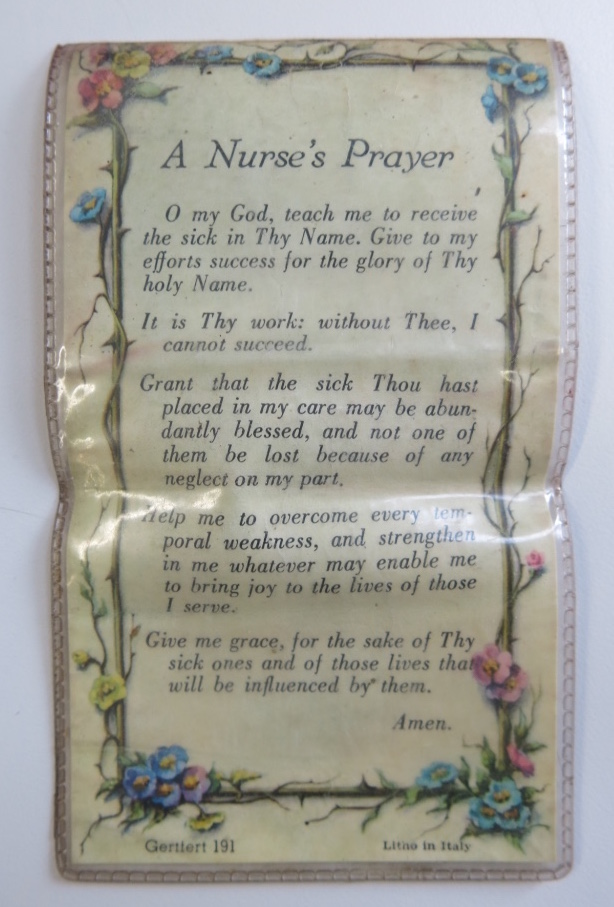

13 Hands

As part of the Who Are You Now? project, Headway East London commissioned the artist Martha Todd to create wax casts of the hands of two of our narrators, both of whom are affected by paralysis and increased muscle tension on one side of their body. The casts intimately record the personal and medical histories expressed in the shape and detail of a hand.

Trudy: When Martha took the cast of my hand, the feeling that I was struck with most was of being paralyzed again. Not the feeling of the stroke as such, but what I was left with after – like the remnants of the stroke. A dead weight on my right hand. No power in it. As if it's dead – no, it's not dead – it's a heaviness. For a split second that feeling was back: "Oh God, my hand.”

I said this to Martha and she looked astonished – horrified even! But it wasn't a sad thing. It was a fantastic experience, it just felt very strange. I'd never felt anything like it since the stroke and the time after, and it was like having something that I could equate that experience with at last: a comparable sensation, yet it not affecting my mind or my memory, so with me still having a clear view of what's going on.

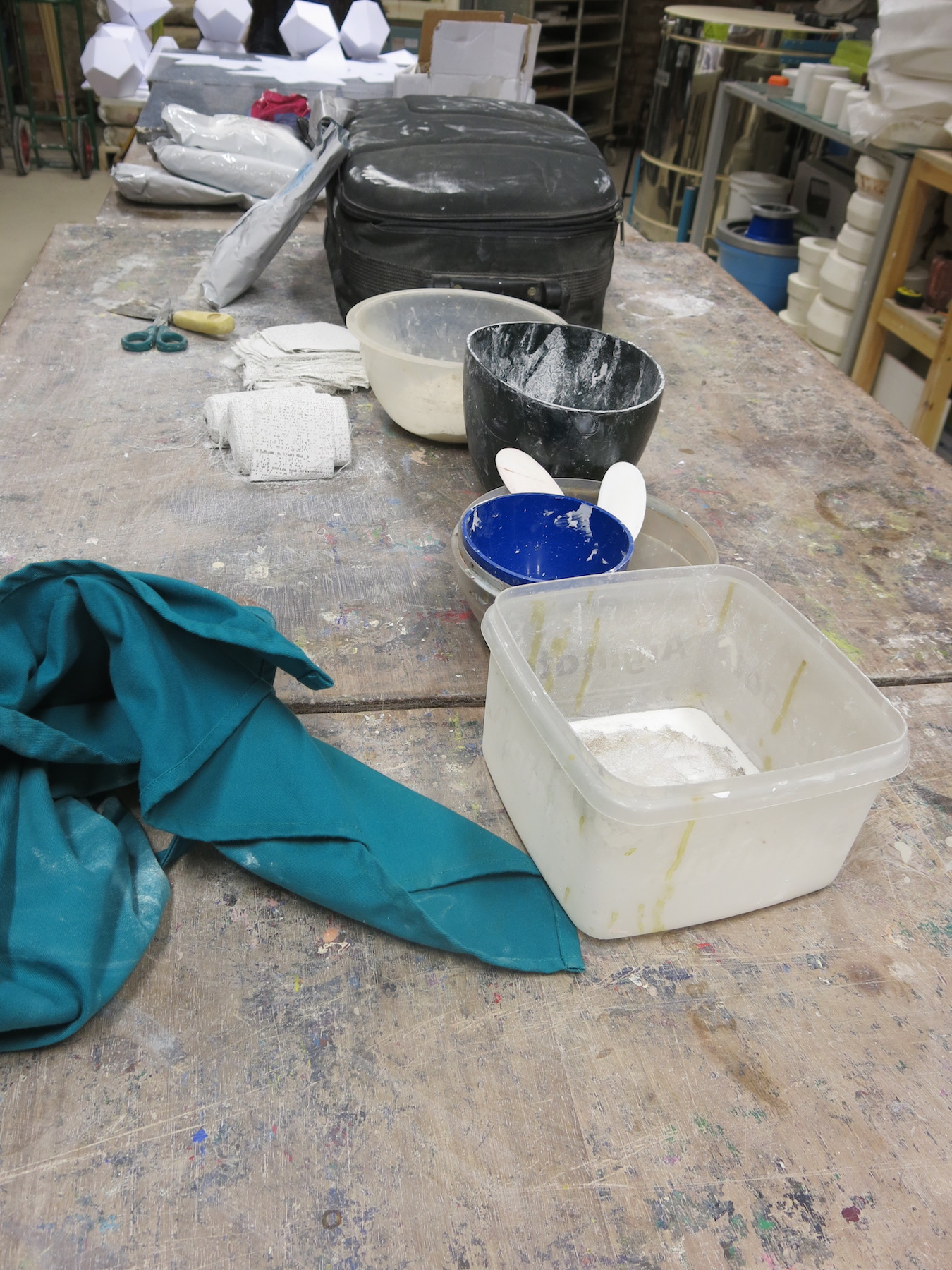

Trudy: As a nurse I've put on lots of plaster casts myself. You work the bandages onto the broken arm, it's wetted a little bit at a time, and then it sets. People have been using plaster of Paris in sculpture for thousands of years. But the fascinating thing is how this technique of sculpture transcended art to become a medical thing – to fit around a broken limb to help it heal. Art is a very healing thing, physically and psychologically. I think doctors and nurses should always open their minds to creativity, to that source of healing.

When I look at the sculpture now, I think, “That's my hand!" I recognise it, and that's it. I always had a wide span, for someone with hands so small. That's why playing the piano came easily to me. It doesn't look so different from the normal hand. Normal? They're both normal to me now. That right hand is a part of me, and I never lost that feeling.

© 'Trudy' / Headway East London (2016). All rights reserved

Hand casts by Martha Todd

Casting process photographed by Emily Manning

To support Who Are You Now? and the work of Headway East London, please text WAYN61 followed by an amount to 70070 or donate online.