After about ten years, I don't care now if I have a fit. Sometimes I know when it's going to happen. If I get to the mirror I can stop it a bit. Talk to myself, talk, talk. But some of them I go through the whole thing. It's like getting strangled. Thank God it's only a minute or two.

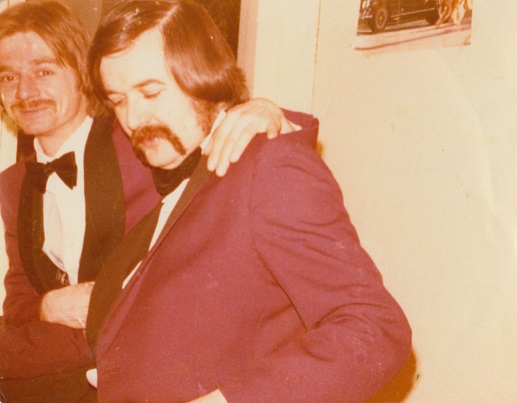

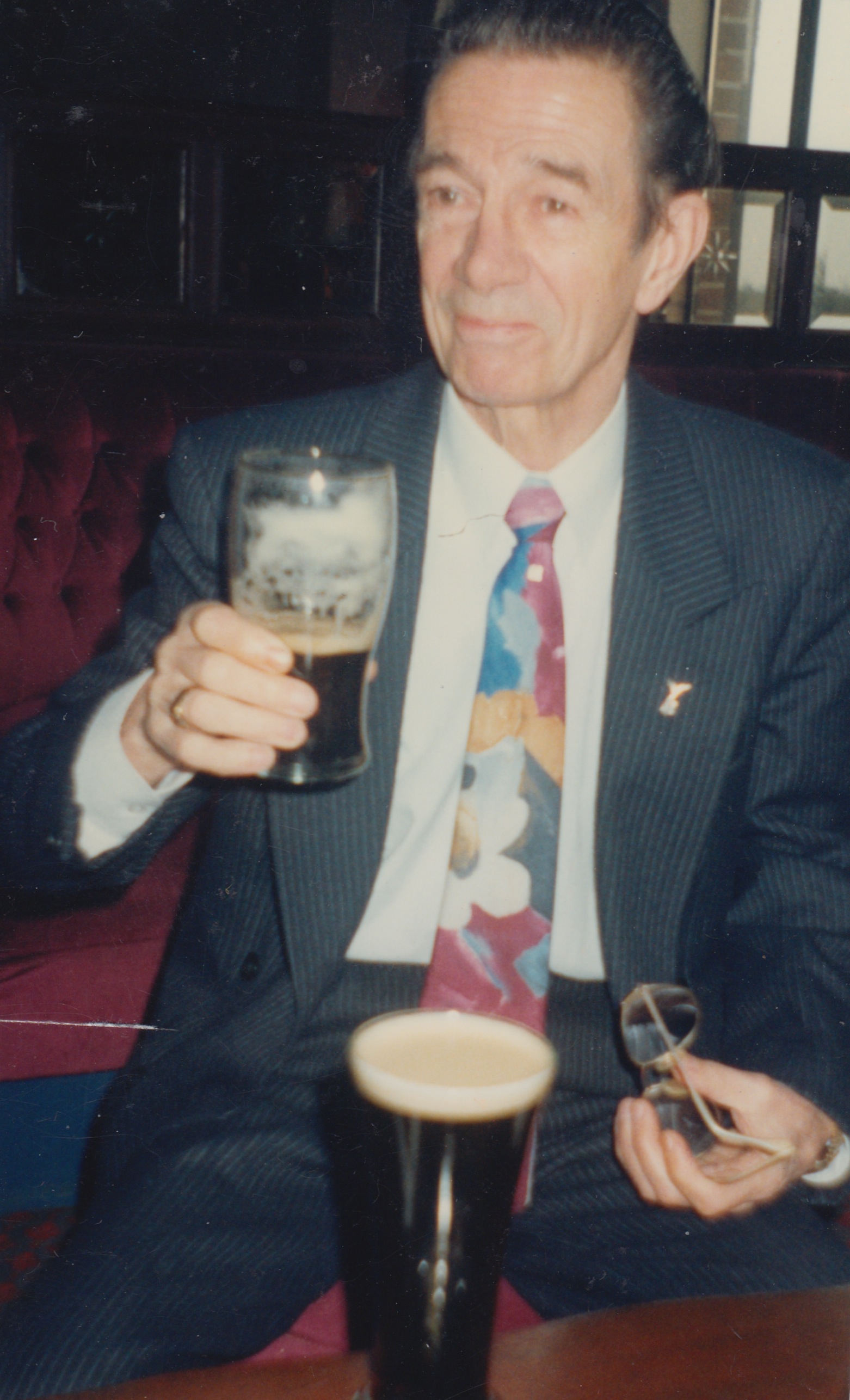

1 A sommelier

I started working as a waiter when I was thirteen. I was a proper waiter. You know, flambé, silver service, everything. In Dublin you had to go to college for three years to be a waiter. Not all the time. It was only two times a week in the winter time, you had to go. I trained as a sommelier as well, a wine waiter.

It was good. You could go anywhere and you'd get a job. You learn a lot about people and how to deal with them. You're meeting people every day and everybody's different.

In the hotels the menus were in English and in French. It was all French food and wines. People would order Crêpes Suzette, and I'd be thinking, 'oh no, not again' because that means you have to cook it at the table. You have a trolley with a gas burner. You need oranges and lemons, caster sugar, butter; then you go to the bar and get brandy and orange curaçao. Go back to the trolley, make the sauce in the pan and then you flambé it. I don't think you can do it now - it's against the law. And there was Steak Diane. That was the same thing – you need a jus and brandy and onions and mushrooms and cream and you cook that in front of them at the table.

It was all rich people – you'd never see anyone from down the street where you lived. There was even a couple of people that lived in the big penthouses on the top of the hotel – they didn't have to do anything for themselves. The laundry was done, the ironing was done. All they had to do was eat and drink and be merry.

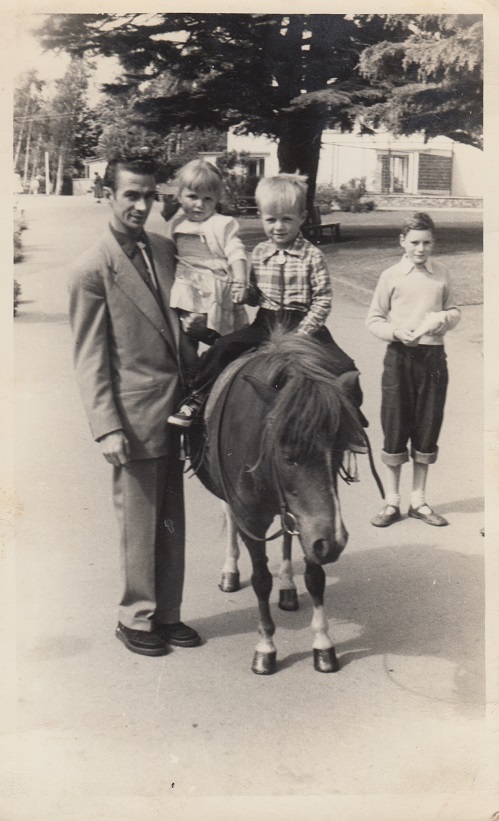

I was born in Lancashire but after three years my mum and dad went back to Dublin. My dad worked all the time. He was a steward and he worked on the ships. Big liners going from Southampton, around the world. He loved it, I think. Great life he had. Going round the world and getting paid for it.

I was the eldest of five. I remember we had one holiday away when my grandfather brought us away to Donegal for a week. My gran came from there, but she never went back up there. I used to run some errands for her, because she lived around the corner from us and I used to get her bread for her and all that. I spoke to her a lot.

As a teenager I think I was getting a bit mad. You know, boys. Staying out late and all this. My mum would say "you have to be in at eleven", and I came in late. Things like that. But everything else was alright.

I remember some of my childhood but I don't know what I've done in between. It's a bit weird since the accident. I know I was a waiter, and where I worked. I know I lived in Dublin until I was eighteen, nineteen, and then I went to England for an interview to work on the ships like my dad.

The interview was on the Monday but the day before that it was Bloody Sunday [1] and the interview was cancelled. The Troubles [2] started then. I remember you got a bit of hassle with the accent.

Instead of working on the ships I worked at the Inverness Hotel near Queensway in London. It was a live-in job. I came over with a friend and we went to discos and all that. It was '72 and everything was changing. Everyone had long hair and platforms. It was about ten years ahead of Dublin.

After a year and a half I went back home. I remember I got presents for my brother and sisters. I got a fishing rod for my brother and tied it on the case.

2 Rambling

I was married in Dublin when I was twenty-one and we adopted one son and then had another. We were married about eight years and then we split up.

I don't know what to say. There's always two sides to a story. I wanted to get away from it all. I think that's what started me rambling. Working everywhere. That's when I went to England again. And my wife started living with another bloke then. She's still with the kids, you know. They're thirty-odd now. They send me cards and all.

I went to Belfast first and I was living with a girl there for about five years. We had a boy and a girl together. And then we split up. It did wreck me at the time. I thought, 'not again'. When I got a bang in the head I did think I deserved it for leaving them.

Not a day goes by without me thinking of everything. This story shouldn't be all me. I mean, I probably caused all that, breaking up.

I went to Scotland. I know I worked in a hotel by the sea. It was in the 80s. It was about 1986, 87. I was not even a full year in Scotland. After the season was over, I moved down to Manchester and then London. But I can't remember a lot of things in between.

3 No money and no cigarettes

Before the accident I was working in a hotel in Reading and I ended up being head waiter there. It was a live-in job. I was caught in a resident's room, you know, so I got sacked for that. I said "what'll I do now?" I went to London then and I was staying with a friend of mine. I don't even remember where he lived.

I wasn't working as a waiter then. I was a labourer. That was before '90. It was Irish people. They were doing building. I met them and they gave me a job on that. They used to pay you £40 a day and that was a lot of money in 1990.

I never had my own place. I was living on jobs and all that. It was alright. I stayed with a lot of blokes, you know. Friends' houses. It wasn't a home or anything like that, it was just work, drinking and dancing. I knew a lot of people in London; friends, you know like – no family.

After that, I was working at another hotel as a waiter, and I had the accident. It wasn't an accident, I got hit over the head, but I call it an accident.

I think I was in the wrong place at the wrong time. Mind you, if it hadn't been me it would have been someone else. So maybe it is better that it was me and not an old lady or something that banged her head. I don't feel sad about it now. I did. Like, annoyed about it, you know, but not now.

It happened in Ladbroke Grove. I just remember seeing two people behind me, with one bag in their hand, and that's all I remembered when I woke up in the hospital a month later.

I know they robbed me, because I was getting twenty cigarettes. I smoked at the time. And I had three pound notes in my pocket. That was the price of twenty cigarettes when it happened, in '90. And that's how I know that's what happened. I remember looking in my pocket in the hospital and there was no money left and there was no cigarettes.

Admission and Discharge Summary

This 37 year old man was admitted as an emergency on 17.08.90. He had been found unconscious on the pavement having sustained a head injury.

He was unkempt. There was no obvious external sign of head injury. His pupils were equal and reactive [3] with normal fundi [4]. He was found to be eye-opening spontaneously and responding to pain on the left side but not making sounds. He had right hemiplegia [5] and right facial palsy. Cranial nerves were otherwise intact.

CT scan of head showed left-sided extradural haematoma [6] with mass effect [7], bilateral intraparenchymal haematomas [8] and hydrocephalus [9].

A left parietal craniotomy was performed and the haematomas were evacuated.

4 I thought I was in a hotel room

When I woke up after the accident, I thought I was in a hotel room.

I seen all these wires. I remember pulling them all out, you know, and then they must've calmed me down. I tried to pull everything out with my left hand because the right wouldn't move.

I just didn't know what had happened. The nurses came in and one nurse I remember explaining everything to me. She helped me a lot.

I'd been in the hospital a month. It could have been two days. I'd a scar from here to there. There were no stitches, it was all staples, you know. Before I seen it, the nurse explained to me about it and then she showed me in the mirror. I said "Jesus Christ". I had hair on one side, and they'd shaved me on the other, and the scar right there, with the staples in it. It's just as well I'm not bald, because if I lose my hair I'd probably end up wearing a hat all the time! So thank God I'm not bald.

I laugh now, but I didn't laugh then.

My right hand was dead. I can't remember crying about it or anything. All I was looking for was a cigarette.

When I was found on the ground, there was no blood. The nurse told me they'd brought me to the hospital and then they realised there was something wrong, so they brought me by helicopter to St Mary's, the neuro hospital. That's when they found out I had two clots, one inside the brain and one outside. I could never find out who brought me to the hospital. I really tried, because I wanted to say 'thanks'. I always thought 'who was it?'

Recently a friend said it was the police brought me to the hospital. I had come off a double shift, afternoon and late, from the hotel. I needed a shave and a shower because it had been a long day. After I had the accident, the police picked me up and put me in a cell overnight as they couldn't rouse me. In the morning I was still unconscious. I was taken to hospital then.

5 Only one other Daniel _______

When I had the accident, no-one knew about it. I remember them asking 'did I have a family?' I couldn't speak at the time. I said 'no', because I think if my mum had seen me at that time she'd have had a heart attack, you know. It would have killed her.

They put a sign on the board in the hospital – did anyone know me? And seemingly enough, they did. A woman was in the hospital visiting someone, and she's seeing my name on the board and she had a son with my name. And she said "there's only one other Daniel ______." She knew my mum and dad and she knew I had to be me. So she rang up my parents. I was out of hospital when they found out, and my dad came over looking for me. I was in a flat by then. He wanted me to come home, and I said "No, I'm not going back." Too many memories over there.

My father, I don't know how he got to me. My mum wouldn't have come over, because she was terrified.

So then, after that, I went over every year. And my dad used to come over here. I don't know, really, how it was for them. As I got better, my mum seemed to be alright about it, but I never asked them, really. I didn't want to give them any more stress.

Stress! I had enough stress myself.

6 I got nothing back

The neurologist said to me "you are very, very lucky" because there was a mass of blood all over my head and they didn't know which way to go (it's twenty years ago, you know, and they are more upmarket now than twenty-odd years ago). They went this side. They done the right thing.

I was in hospital for six, seven months. I had to learn to move my right hand side. And then when I came out I had to learn how to speak and walk again. The walking took about three or four years. The speaking I'm still learning.

The neurologist said to me about when something happens to your brain, everything here tries to get over here to help repair it. It can heal itself, so I'm lucky really. I can use my hand again, but it's still not right. They told me I'd get to a point that I can't get any more back, with my speech and all that. Because some of the brain cells that I have lost do not reproduce. If someone asks me what's wrong there I say it's like a river with no water in it.

Even now, I can't run. If I run I go to the right all the time - I don't know why. See now, along my right leg I can't feel all that. Just the top.

The doctor told me I would never work again, because I had epilepsy as well. I was devastated. Devastated... I just had one thing in my head, I was never going to walk properly.

They discharged me from hospital and put me into a hostel. So I am living in Whitechapel and I have to go to Ladbroke Grove for speech therapy. I get to Whitechapel Station but I can't speak. I can't say where I'm going.

I knew I was going to Ladbroke Grove. But I couldn't read. That was gone. And I couldn't say 'Ladbroke Grove'. I knew where I was going and I was paying for it and the man was getting annoyed with me. So I went back to the hostel I was in and they wrote it down for me then. And when I got there I missed the appointment. It was things like that, you know.

I was given a key worker to go to appointments as I wasn't able to arrive there or come back. I don't know if that was before or after the Ladbroke Grove thing.

7 Fraggle Rock

When I came out of hospital I remembered that maybe I was wanted by the police. I went to the police station to get sorted, because I knew I was charged with something. I said, "I think I'm wanted for something, and I don't know what it was," and they told me. It was the stickers.

Someone offered me £25 to put stickers in the telephone boxes. And I done that and I got caught. I was arrested. And after that I had the accident. I didn't turn up in court – I was in hospital – and it's only when I come out of hospital that I remembered something.

When I went to the police station, I couldn't tell them or show them what happened. It was just after the accident and I couldn't speak like I can now. I was brought to court and they remanded me in custody for two weeks. They put me in custody because I couldn't speak properly and I couldn't explain. They brought me in a van to Brixton Prison.

I was having a lot of fits. After I was taken into custody, I wasn't taking any epilepsy tablets, because I didn't know what they were called. I actually thought I was getting brought there to get executed. I had about twenty quid and I gave it away. I thought, 'I don't need this'. I really thought I was getting executed. Imagine that.

I didn't remember who I gave the money to. But someone used to come along and throw cigarettes into my cell. I don't know who it was.

I'd forgotten about all this.

They put me in the cell and after three or four days I must have come back to my senses, because before that I couldn't remember what was going on. It's called Fraggle Rock, this block I was on. There's people go in there that have mental problems. And then they put me in a double cell. There was another man on the top bunk. The first night, when I woke up, I thought he'd pissed in his bed on top of me. But it was blood all over me. I thought it was me bleeding. I started screaming.

He'd committed suicide. Well, I don't know whether he died or not. I'll always remember it.

I don't know what happened after that, but I went in the court after two weeks. The judge turned around and said to me, "you look a lot better this time". And he gave me a conditional discharge.

When I got out, I went back to the hospital where I had the rehab: St Charles in Islington. I didn't remember I'd been staying in the hostel, after the hospital. I had to find out. It's a bit weird, really.

8 They couldn't see anything

I went for compensation for the accident. I got nothing back. When I came in there, the policeman should've been there and my solicitor says to me, "we just got a phone call that the policeman won't be here, he's not well. Should we go ahead with it?" and I said "yes, it's straightforward. I got a bang on the head."

They said I could have fallen. The nurse from the hospital said "yeah, he could have fallen, but it had to be about three storeys to get the damage he had." So the judges went away. There were three judges, one, two, three, and they came back and said "no, we don't believe you were hit on the head", because they couldn't see anything wrong with me.

But about that as well, I'm glad that I didn't get any compensation, you know, because I don't think I'd be here if I'd have got money. If I'd got something like £35,000 in compensation I wouldn't be able to deal with it. I'd have probably hit the drink with that money. Holidays, everything. I was annoyed at first, you know. I thought 'ha, they don't believe me'.

At the time, you couldn't appeal. You could, but it would cost you money and I had no money at the time. They said you'd have to pay for it or else you'd no comeback on it at all. It really annoyed me for a long time.

After that, I got compensation for being ill, you know? What's it called? Something to do with benefits. I get that but I get the lower rate, you know, not the higher rate, because I can walk. When I look at it now I've been getting that benefit since '96 or '98, something like that.

9 I couldn't do it

In the nineties I tried working to get money. I went to an agency and gave them a dodgy name and said I was a waiter, you know. And when I started trying it, I couldn't do it. There was one do, was all, and I had one table on it – twelve people. So I put the starter on, took that off and brought the main course. But I put them on the wrong table. I couldn't remember what table I was doing.

It was straightforward. Everything was on plates – it was just bang, bang, bang. If it had have been silver service I wouldn't have been doing it.

I couldn't do it. I tried it a couple of times but it just didn't work. It whacked me completely, you know, mentally.

10 The episode with the cow

I never drank heavy before the accident. I drank more, after. I think I was using the drink to feel I would be okay. I used to be terrified of having fits. If I thought I was going to have a fit, I'd drink, to put me to sleep.

I haven't drank now for five or six years. I looked at myself and I thought, 'you've gone through all that and you're not going to die from drink'. I was taking tablets for epilepsy as well and the tablets weren't working, because of the drink.

I stopped, then I started drinking again, but then I stopped it again. It was no big deal... well, no, it was a big deal. I didn't stop it just like that. The doctor told me to come down off it easy.

I think it was partly the episode with the cow. See, what happened is, I woke up one morning and said "look, I'll take my tablets and then give it a while and I'll have a drink". I had a couple of beers and I went to sleep and I woke up and I thought it was the next day. And the next day, and the next day. So I took the tablets three times in one day by mistake.

The fourth time I woke up and it was just wacky. There was a cow sitting in the middle of the room, talking to me. I was talking to the cow, then I was sitting on the sofa and the sofa started moving, and I see five people in the sofa, moving. And I said, "I have to get out of here". So I went outside and I felt truly weird.

A friend of mine, Mary, she came around to see was I okay and as soon as she saw me she said "oh, you're still drinking." I told her what happened and she got the ambulance.

Mary has been there forever, you know. I met her in '91. We clicked it together but it didn't work because I started drinking. I didn't see her for years and then I seen her again.

We used to be a thing but now there's just that we're friends and she comes to my place most of the time. She's staying with me since the bad fits I've been having lately. She's helped me out. Oh hell, I'd be dead only she found me a couple of times.

I got rid of the drink but even now there hasn't gone a week that I haven't had a fit. I said "how long till I can come off the medication?" The doctor said "if you are two, three years clear of fits, I will take you off the tablets forever."

Because I haven't been well for the last couple of months, Mary's been there more or less all the time. She don't get paid or anything like that, you know. I am terrible with leaving the oven on. I cook, but I have to be really careful. She put signs all around, you know like "don't forget…", "switch off…", "don't forget your keys". She's okay, you know.

11 Back to normal

When the social worker brought me to sign on, I didn't know where I was, because I had worked all my life and I didn't know anything about the dole. And I thought it was horrendous, you know. But it did help me out.

They helped me out with a place to live as well. I was in the hospital for so many months, and then I went to a hostel and then another hostel and another hostel until I got this place now, a one-bedroomed flat. You see, in between that, I can't remember what happened. I was in a hostel sharing a flat with another man, a drug addict. I'm in one room and he's in another room and we share the kitchen and the bathroom. After that, I got a one room flat in Hackney. It was to do with an organisation called Single Homeless Project [10] getting me back together again. If you turned around you'd hit the door, you know, it was so small. But it's the first stage of coming back to normal. So, I'm in there for a year and a half. I know that. And next I get a letter from the housing people: would I view a council flat? It was only up the road from the other flat, and I got it. I've a garden as well, and I've alarms everywhere. It's secure. I think I've been there since '94, '95.

I'm finally at home now, you know. I've gone back to Dublin but I wouldn't stay there. No, I've been over here too long.

There's a lot of people that have helped me out over the years. I'd like to thank them, but I can't remember all the details.

12 I should have been a bleeding policeman

I don't go out at night time. I imagine someone behind me all the time. And I won't get on the bus unless it's empty at the back. I have to be at the back so I can see no-one's behind me. I always think I'm getting robbed again. I think I should have been a bleeding policeman, because ever since the accident I watch and look at everything.

The only, only time I go out at night – I'll be honest. If I need cigarettes I'll go out if it's dark, if it's four o'clock in the morning. If there's a storm out there I'll get them.

When things are bad I go to sleep! I sleep in the afternoon, but I don't sleep at night time, that's the bleeding worst of it.

I get very uptight all the time, you know? No patience. It's so silly, I can't wait for a boiled egg. I'll fry it first, it's quicker.

I did have patience before. Well, I think I did, because a couple of people have said to me "you've lost your patience". I said "I'm getting on, I'm sixty, bleeding hell!" and they said "no, no".

If I'm waiting for a bus I won't wait, I'll walk. Things like that. And queues. There's no queues any more on buses. I got into trouble over that. I was waiting, and the bus comes and a load of people go in front of me and the driver said to me, "no more, no more" and I was the one waiting. So I sat in the road. I said "I'm not moving until I get on" so then two fellows came out and lifted me up and put me back! I just won't give in, you know.

There was a bus behind it anyway, so I got on that one.

I'm impatient with a lot of things, but I am patient with people to an extent. If I do get on a bus I'll always stand up and give someone else a seat, you know. If a woman's getting on I'd give her a hand with the pram, or anything like that.

I'm very soft really, you know, underneath it all.

13 The buzz

I've changed. I know I've changed but I can't remember what it was. It's hard to consider. I can't remember. There's nothing there, really, when I look back.

When I'm sat on my own I say to myself, 'I don't think I have changed.' It's just I never had that buzz. I remember when I was younger getting that… waiting for something, right? It's like at Christmas. Like holidays and all that. I remember being really, really happy – you know? And I have never got that since. There's something missing. I'm a bit harder. I can laugh and all that, you know, but I'd love to get back that feeling.

I'm not feeling sorry for myself. I've had a bonus the last twenty years. So every day, I have to keep that in my head. I mean, why am I alive after all that? I'm here. That's the way I look at it.

14 I really don't know what to tell them

Anyone, anyone out there, they just don't get it. They might see people getting better on the TV and all that, but that's it, they don't know how hard it is. I don't know how to explain. I suppose sometimes I'm okay but most of the time I'm not.

I really don't know what to tell them. I think it's only when something happens to a family – that's the only time they'll know all about it. Like what happened to Schumacher. He still hasn't woken up yet, you know.

My doctor knows about Headway, but a lot of people haven't a clue about Headway. They really don't. I had never heard of it. I found out about it through this alcohol rehab place. I'd stopped drinking, and they told me about Headway. So I got an interview through my doctor. I don't know how long I've been going here. Probably two or three years.

There was a lad who used to come here, and I used to see him where I live and I just talked to him. I didn't know he had a head injury and he didn't know I had one. When I came here the first time, he was here and he said "Ah..." That's how I mean. A lot of people, they wouldn't tell anyone even when they come here.

I'm glad I told you about it all, you know. I just hope it will help someone else, I really do, because people don't know about it, and I can think of a lot of people that are like the way I am now.

At the hospital, there are so many people involved, just to save one person. If I can help one person to know that you can get better, that's alright with me, you know?

15 A little good thing

Headway is like coming into another world. You come in and you sit down and you feel normal. It's brilliant. I can't explain it, the feeling. I wouldn't be able to talk like this if I was outside. I don't feel the same as I do when I'm here. My patience is terrible but I'm patient here. I've just never seen one of the staff on bad form. Never. There's no-one on bad form here. It's helped me a lot, for outside.

I spoke at an epileptic thing a couple of weeks ago [11]. It's for epileptics to listen to other people's experience. And there was a surgeon there. I just told them what happened to me, and how I felt about being an epileptic and all that.

I found I got a little good thing still in my head, coming out. Especially here, now. The speech is still a bit wacky, I know that. Some things will come out wrong but I don't mind these days.

Yesterday we prepared all the canapés for the art show [12].We plated everything on salvers and we took them in to the people. The canapés were smoked salmon, and quite good they were.

It brought back memories. How do I put it? I'm trying to think of the words. When I was working as a waiter I used to get a buzz out of it. I didn't look at it as a job, even though I got paid. The money never came into it. I just enjoyed doing it. And the same here at Headway. Doing it is brilliant. It gives me that buzz. You're back meeting people again. I know I can't go back working in a hotel or a restaurant again, but I can help people out doing it here.

Last night I got a lift home after the art show. I said 'I just live there.' After she left, I had to walk about fifty yards. Like I said, I don't like going out at night time. It's only since I've come here I'm starting to go out on my own at night time.

It was like 'I've done it!' I don't know what the feeling was. But I was delighted when I got home. Delighted that I'd done what I'd done.

I remember we done a dinner in the art room [13]. I think it was this time last year. The chef was involved from the River Café and he was quite good, you know? Everything was cooked in the new kitchen and then we transferred it into the arch where the people were waiting. Years ago I'd be embarrassed going into places like that.

Everyone loved it. They were nice people. I think the money that they're giving – they know where it's going. They're involved with what we're doing.

It's opened me up a bit since I came here, because a lot of people here are like me. When I came here I said 'now, think of other people, because you know you're alright. And they need help more.' I can see the difference in people here, in two years. And if I can do it some of them can, you know?

There's one man in there, right, all he can do is that – one hand. Lovely fellow, he used to be a chef. I won't tell you what happened to him, but he's paralysed. He can't speak, but I talk to him. I know what he's saying and he knows what I'm saying. I know he can only blink but I know which blink is which. Two is 'yes', 'no' is one. I started talking to him when we were on an outing – outside of London somewhere. I knew he was a chef and he didn't know I was a waiter but when I told him I was a waiter he was laughing. You know. Brilliant.

* Daniel passed away on 27th December 2018. He is greatly missed. This story is dedicated to his memory.